Chaïm Soutine (1893 - 1943)

Portraiture

Soutine continued with the genre of portraiture until his last day, and his destiny as an artist was bound with it. As a youth, he drew the portrait of one of the residents of his native village, an act which led to corporal punishment from his father.

In 1915 he met Amedeo Modigliani in Paris, and their close friendship left a profound imprint on Soutine’s work processes. Modigliani’s impact is discernible in his portraits in the composition and the positioning of the figures. The merciless realism in his depictions of women—sweaty, disheveled, intense—he may have learned from Courbet, whom he admired. In the unusual technique of his portraits Soutine sought to articulate the essence of the person before him. Many of his paintings feature faces rendered in full or in 3/4 profile, and highly expressive hands, which, for him, were charged with no less meaning than the face.

Soutine rarely painted nude models. He was not interested in physical beauty or ugliness. On the other hand, he was intrigued by men in uniform, whether the work clothes of a baker or the livery of a bellhop in a hotel. Representative uniform, overalls, or an apron erase individual uniqueness, making it hard to discern the personality behind them, thus challenging the artist. At the outset of his career, Soutine painted numerous self-portraits, and one of these early works is included in the exhibition. Even his portraits of others, however, often convey the artist’s own temperament at the time.

Landscape

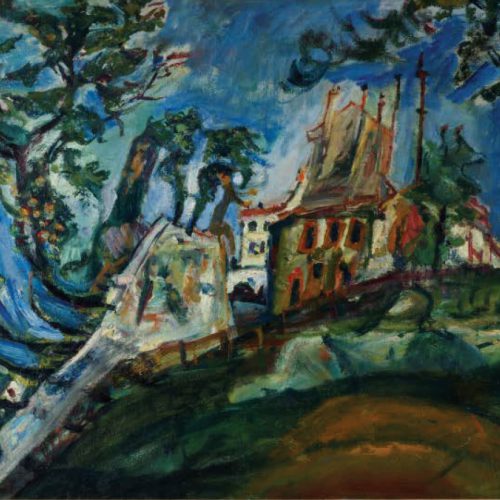

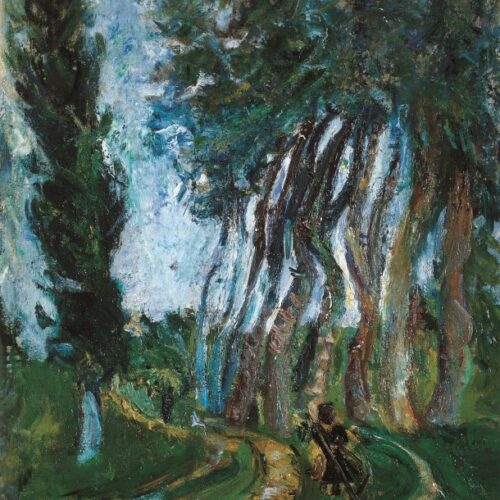

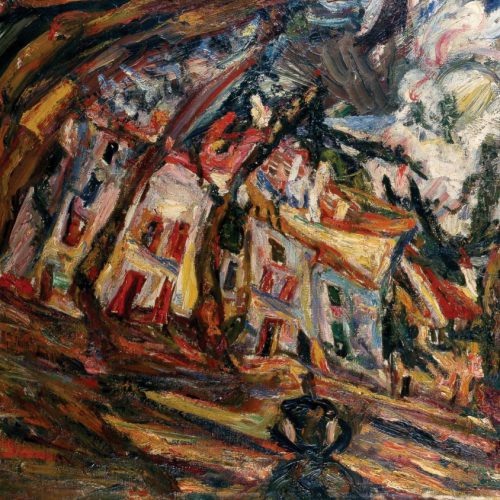

Sent by art dealer Léopold Zborowski to the village of Céret in southwest France in 1919, Chaïm Soutine began working on landscape paintings. In 1927 he shared his opinion on his Céret landscapes in a letter: “I never related to Cubism, even if that style enchanted me for a moment. When I painted in Céret and Cagnes-sur-Mer, I was influenced by it against my better judgment.” Soutine, however, did not distort nature unrecognizably as did the Cubists; he tyrannized it. His close friend Marvena noted that Soutine’s devotion to nature was too great to enable him to devote himself to abstract art.

While in his still life paintings, Soutine heeded every detail, his landscapes were more spontaneous and resonated profound emotion. Breaking away from the academic rules of landscape painting, he presented the place as he saw it, using it as yet another means to convey his view of the world and cast his inner world onto the canvas.

While Soutine himself was not proud of his Céret landscapes, they enable us, today, to trace his painterly development: they grew gradually more deconstructed, and the sophisticated composition no longer obeyed existing rules.

Having “escaped” Céret, Soutine abandoned the landscape genre for years, returning to it only in the 1930s. The views of Chartres and other landscapes he depicted towards the end of his life differ sharply from his early paintings: they no longer surrender the same passion, the same powerful emotion, typical of his nascent work.

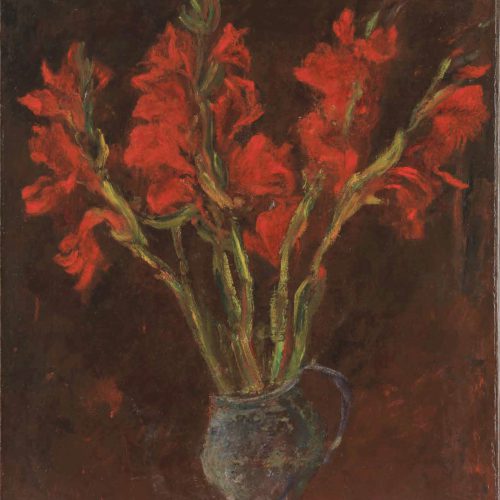

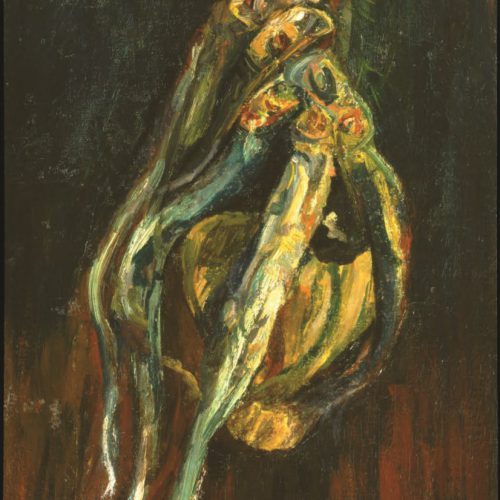

Still Life

Chaïm Soutine had engaged with still life in his early work, but his true power in that genre reached its peak in the 1920s, in an outburst of creative energy and internal freedom. The still life paintings he created in those years, with emphasis on dead animals, earned his reputation not only in the artist community, but also in the art critic and art collector circles. The general recognition and the subsequent escape from poverty enabled him to work as he pleased and to develop a personal artistic language.

Soutine’s still lifes may be divided into two distinct periods. In his early works, as a poor shtetl youth newly arrived in Paris, he depicted mainly kitchen utensils and the plain food of the impoverished: herring, leek, shabby plates. In that period, in which he has not yet developed a style of his own, Soutine’s paintings show Cézanne’s clear impact. In his contemplative or metaphoric still life paintings created after 1925, on the other hand, one may detect the work of a mature artist, and the influence of Rembrandt and Chardin. Soutine was drawn to the texture and colors of the meat, and his best-known series portrays beef carcasses which he painted in a frenzy. He hung cuts of meat from the studio ceiling and waited for them to ‘ripen,’ namely—begin to rot, and only then did he depict them on canvas. He was fascinated by the changing hues of decay.

For Soutine, still life was not an allegory for man’s power, as was the case for 18th century artists who portrayed wealth and status in paintings which attested to hunting skills and material success, or the vanity of such power. This genre enabled him to express himself in the most revealing manner, and thus present not only his artistic path but also his own self-image.

Andrea Wine and Gershon Silbert, Israel, Wendy and Harry Kantor, USA, Tsila and Giora Yaron, Israel, Anonymous in honor of Monique Birenbaum, USA, Arkin Foundation, Israel, The Herschmann Family, USA, CBH Compagnie Bancaire Helvétique SA, Outset Contemporary Art Fund, RAMON–GRANIT / TOREN Marine Insurance Agents

Naked Soul: Chaïm Soutine

Curators: Suriya Sadikova, Dr. Batsheva Ida Goldman, Yaniv Shapira