A person worries about losing his money / But he does not worry about losing his days / His money does not help / And his days do not return

(Adam doeg al ovdan damav / ve-eyno doeg al ovdan yamav / damav eynam ozrim /

ve-yamav eynam hozrim)

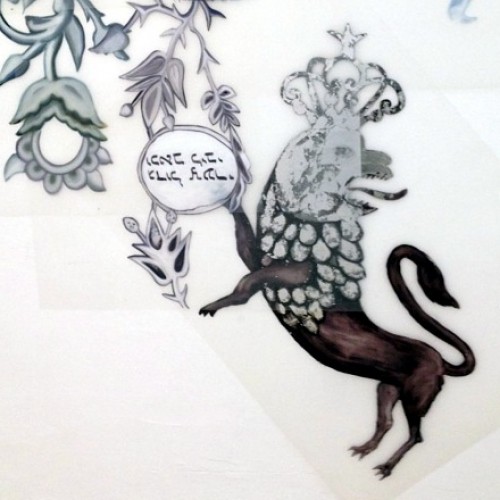

This verse [composed of two rhyming couplets, the first in tetrameter and the second in trimeter (Tr.)] can be found inscribed or painted on old “Shiviti” and “Mizrach” papercuts that were hung on the eastern wall in synagogues and homes.

In a dialogue that Ayelet Carmi conducts with one of these papercuts that forms part of the Ein Harod Museum’s collection of Judaica, her attention is on an error that appears in it.

Instead of “eyno doeg al ovdan yamav” (“he does not worry about losing his days”), the man who made the papercut wrote “ani doeg al ovdan yamav” (“I worry about losing his days”). Something personal: perhaps he really did worry. Men ornament [papercuts] and worry about money that doesn’t return.

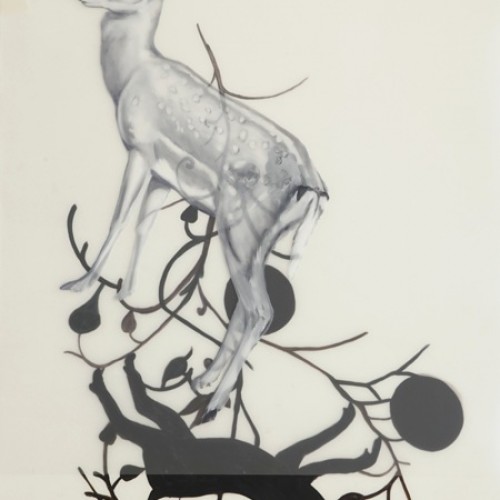

Using cutting knives, they created marvellous animals and plants, a heraldic structure, the right and left side facing and reflecting one another, while Ayelet Carmi turns it topsy-turvy to create a new order.

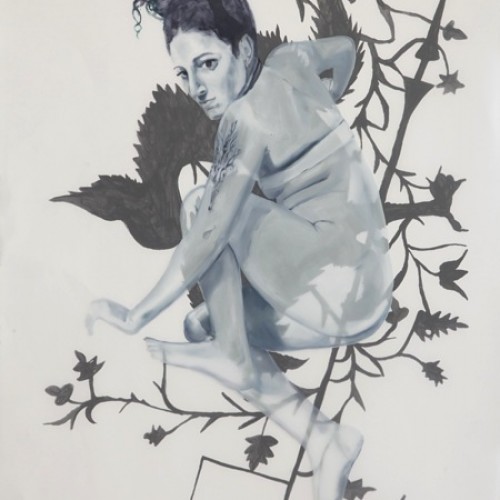

Ayelet Carmi’s work, with its large dimensions, seems to be suspended from a thread; it is all parts that come apart, touching and reflecting one another, all of it fragile paper, here and then gone. The original papercut contained a textual error. Ayelet Carmi ravages the papercut’s structure. She gives free rein to the fantastic vegetation and animals, which can now run like a deer and be brave as a lion, taking on one form and then another: a woman juggles them.

What began as a flat, heraldic papercut, the right and left sides symmetrical, has become animated with body and sensuality, a hybrid poetic structure.

Ayelet Carmi is the inventor of a new genre of painting all her own. Cleverly escaping the entrapments of traditional painting, her work engages in a deep and thoughtful dialogue with relational depth patterns, its highly sensitized nervous system producing art that is nuanced, lightweight and fragmentary. Often using a layering of transparencies, her works echo a multitude of times, realms and places. It is a body of work decidedly of its time, sophisticated and witty.

Already in her work from the early 1990’s she begins to elaborate her own version of the ‘myth of the artist’ – a formative narrative whose shadow is cast wide and large over the history of Western art since the days of Vasari in the sixteenth century, and where room for female artistry was all but nonexistent. Boundless and deeply personal, Carmi’s version of this myth is channeled through the female nudes that dominate her work, women whose brushstrokes continuously recreate a world in painting – recreating but never appropriating. Essentially open-ended, her works come together and unravel as they echo a painterly realm suffused with architecture, politics, rites, theatrical sets, imagery and identities.

Carmi should be seen as an artist-inventor, always coming up with new painting techniques, installation strategies and three-dimensional structures. The female figures that figure in her work cleverly challenge the principles of painterly representation, confronting the themes of two-dimensional, art and life, the embodiment of the spirit, and the then and now.

Ayelet Carmi

A Person Worries

Curator: Galia Bar Or

November 2013- February 2014