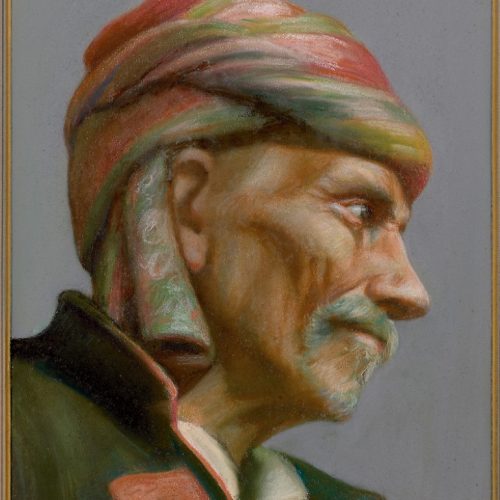

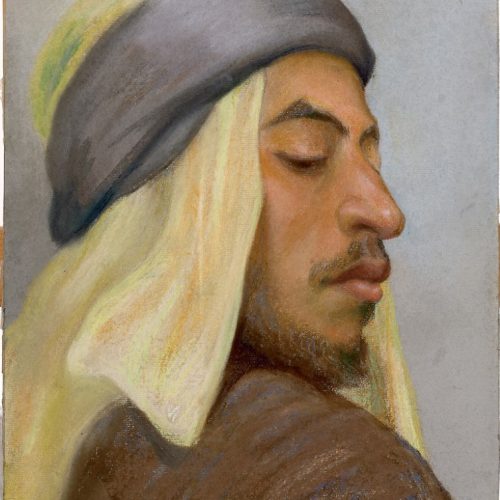

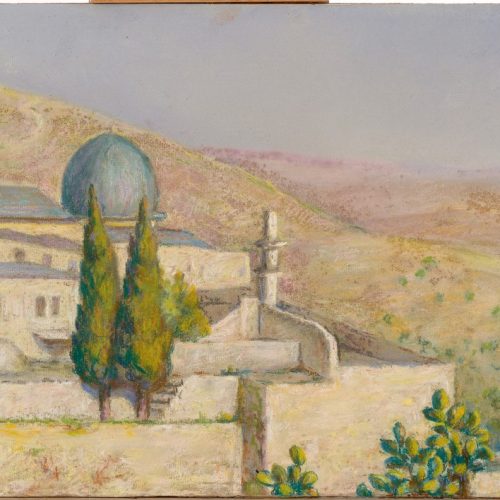

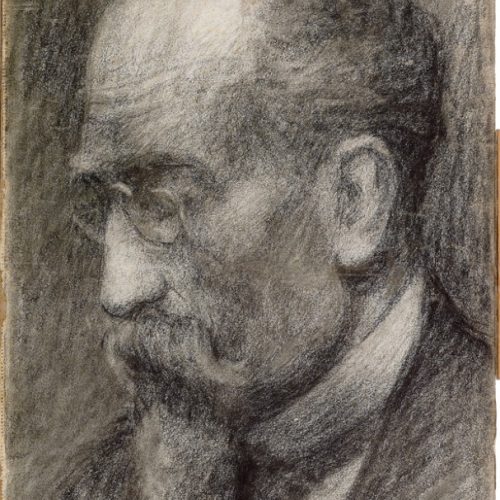

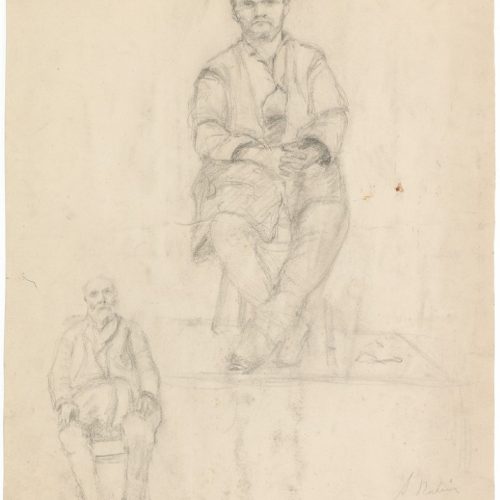

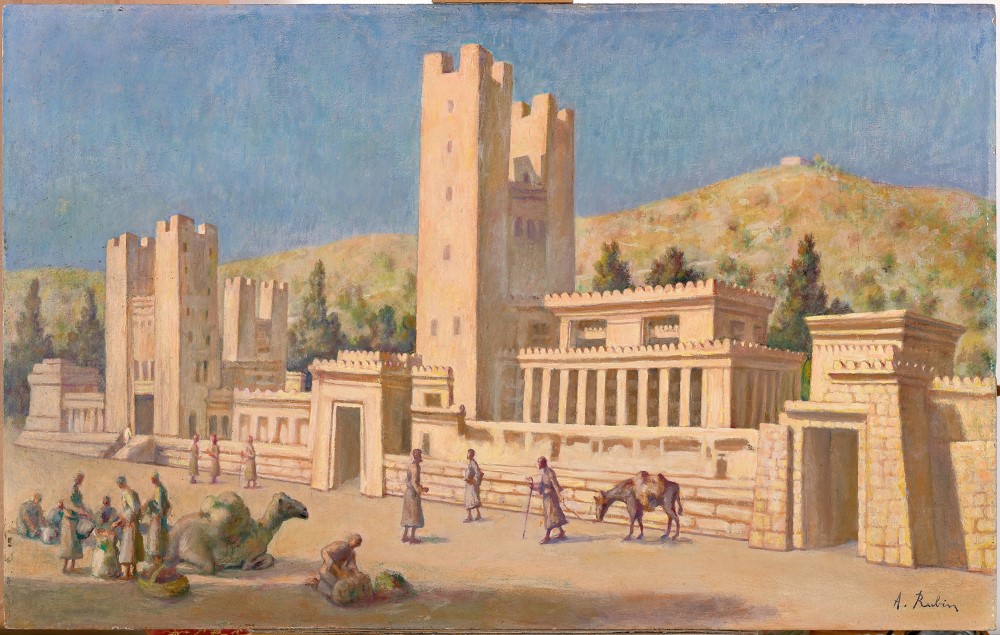

Spanning across a half century (1906- 1956), Albert Rubin developed and practiced his artistic talents as a painter, a sculptor, a graphic artist and an illustrator. For this special exhibition, however, we have chosen to focus mainly on the first four years of his work: his three years in Jerusalem at Bezalel (1906-1909), and the drawings he created in his first year of study in Paris with Fernand Cormon, shortly after he left Palestine.

Although until recently Israeli researchers preferred to focus on “luminaries” such as Reuben Rubin and Nahum Gutman, who had at one time or another attended the Bezalel School of Arts, it would seem that now we should spotlight other artists from the school of Professor Boris Schatz, Albert Rubin among them, who did not toe the Zionist ideological line, left the country and tried their luck in the Diaspora. Creating the “national-cultural legacy” was and is a Sisyphean task, and much still remains to be done. Indeed only now are we beginning to truly detect a trend to expand the canonical discourse of Israeli art, follow the growing diversity of activities in museums, and revel in an expanding shelf of relevant albums and books

Just a few fortunate ones have had their artistic legacy treated in a professional and vigorous way, with most rooted in our memory solely due to the museums bearing their names, devoted to their art, and commemorating their work, such as the Reuben and Nahum Gutman Museums in Tel-Aviv, the Janco Dada Museum in Ein Hod, the Anna Ticho House in Jerusalem, the Frenkel Museum in Safed, and the Castel Museum at Ma’aleh Adumim. Descendants of artists who have been shunted to the margins of memory tightly hold onto their works within the family while contemplating how to deal with their inherited heritage, and the importance of the legacy left to them. To preserve their works? To display them? To sell them? To document them, or perhaps just let them slide into oblivion? Who can tell if one artist or another will suddenly burst forth from obscurity or not? Does the fact that an artist is presently unknown portend that he or she is also doomed to oblivion in the century to come – and that if no one should ever take an interest then perhaps any effort invested in them would simply prove to be a waste of time?

The Museum of Art, Ein Harod, has often undertaken to revitalize the memory of forgotten artists, such as Asher Feldman of Rehovot (who did not attend Bezalel), and others who followed their craft in kibbutzim and towns throughout Israel.

Albert Rubin serves as a point of departure in giving us the opportunity to appraise a fascinating but little-studied artist, who ipso facto represents all the students of the inaugural class at Bezalel, and thus offers a rare opportunity to scrutinize its core: What did the students paint? How did they work? What was the nature of the ambience that Boris Schatz created around himself?

We sincerely hope that in the future we will continue to enjoy expanded discourse on this significant event in the life of Professor Schatz in particular, and the emergence of Israeli art in general, a topic which has been justifiably attracting increasing attention and curiosity in recent years.

Reaching beyond the research and assembly of the collection, we have also included selected recollections written by the artist’s children. Sylvia Chetrit, his daughter, broadly surveys the story of his life, his wanderings, successes, raising a family, and laudatory articles found in professional literature in Paris and other places. Some years ago his son Claude published in Paris an intimate family book, “Kaddish for Two Hands”, which he dedicated to his father.

We include here only the first four chapters of the book, mainly describing the uncompromising struggle of the young Albert during his time in both Jerusalem and Sofia, but mainly in Paris, the struggles of daily life and making a living, hunger, anti-Semitism, and even enticing offers to engage in forgery. The fourth chapter ends with Rubin’s struggle with the Spanish flu that ravaged Europe in 1918, killing millions (among them, the young Austrian painter Egon Schiele and his wife Edith). These chapters most effectively describe the period covered by the exhibition, and through which Sylvia seeks to perpetuate the memory of her late brother Claude, allowing us to view this excerpt as a “Kaddish for Four Hands”: those of Albert, and those of his son Claude.

We would also like to extend our deep appreciation to the Chetrit family – Sylvia, Daniel, Gali and David – for their considerable help and assistance.

Albert Rubin

Beginnings

Curators: Galia Bar Or, Doron Lurie

June-August 2010