Since the early 1940s, Azaria Alon has repeatedly introduced himself to the desert landscape – a whole world unto itself, inexhaustible in its aspects – and addressed it with all his might as a researcher, an educator, an activist in the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel (SPNI), a lecturer on his regular radio program, and more. From the wide variety of topics Alon has dealt with, we decided to limit the selection of photographs to a handful, starting with the subject of desert excursions, which opens the series of photographs in this catalogue. This series connects to a second sequence of photographs, kibbutz portraits and landscapes, a subject of great importance in Alon’s ongoing work in photography, which he has yet to integrate with texts of its own. We decided to accompany this sequence with a section from Alon’s autobiography that is a profile of sorts of the kibbutz, its people, and its landscape. The same spirit of the times permeates both the photographs of the desert and the kibbutz landscapes; it seems to invite one to linger and immerse oneself in gestures and details, to contemplate the individual and the group. From the contemporary perspective of the days of privatization, this sequence of photographs evokes new thought-provoking elements, and perhaps also reflections on the significance of togetherness, the essence of the affinity between ideology and culture, and the complex relationship between personal and collective identity and place.

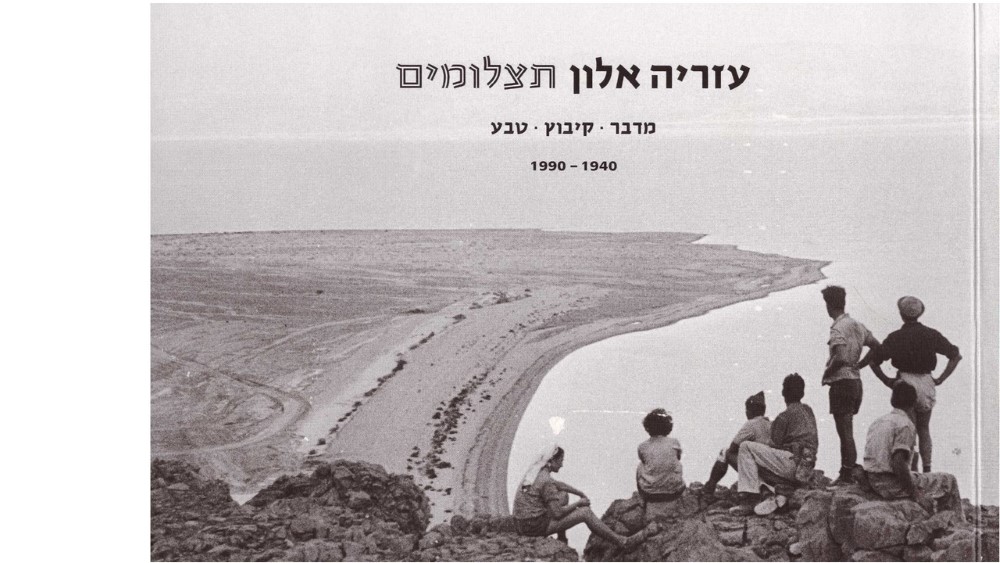

Finally, a small group of photographs was selected to represent a rich spectrum of topics and many years of activity: the nature photography for which Azaria Alon is best known. Here we focused on a select group of photographs of trees. This sequence, which appears to merge the portrait and nature photographs, completes the triumvirate of subjects, “Desert, Kibbutz, Nature.”

This triple exhibit is displayed simultaneously at two adjacent museums, Beit Shturman and the Museum of Art at Ein Harod. Avital Efrat, Galia Bar-Or, and Guy Raz joined together to curate the show, which is accompanied by a joint catalogue.

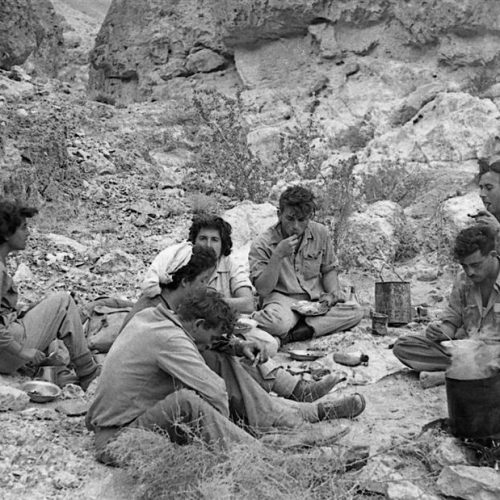

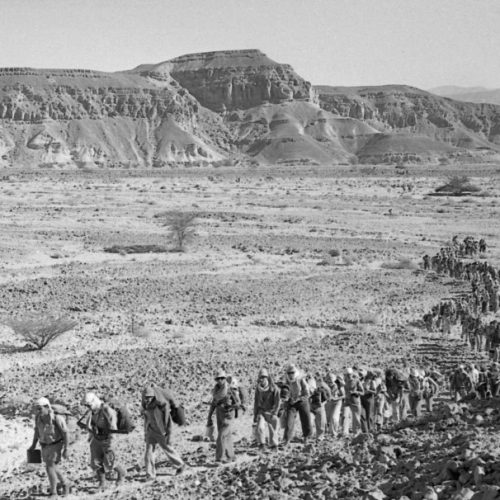

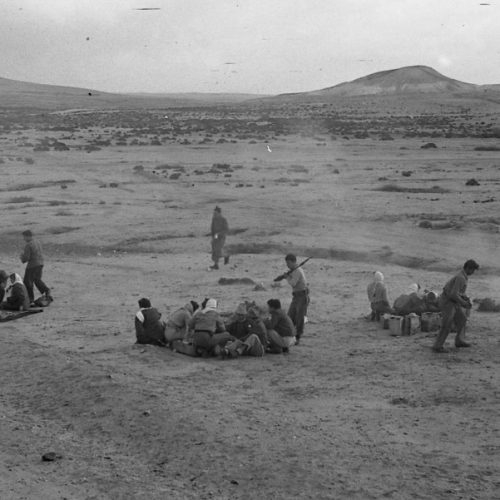

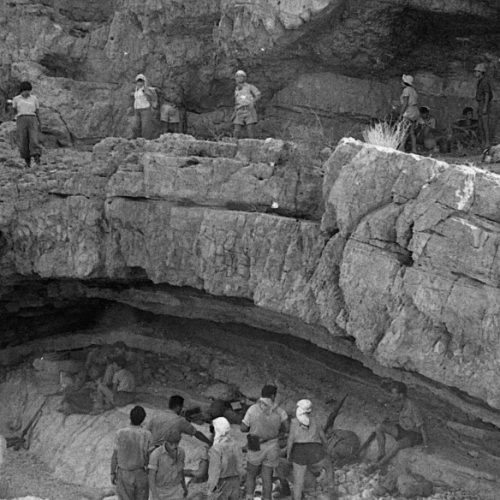

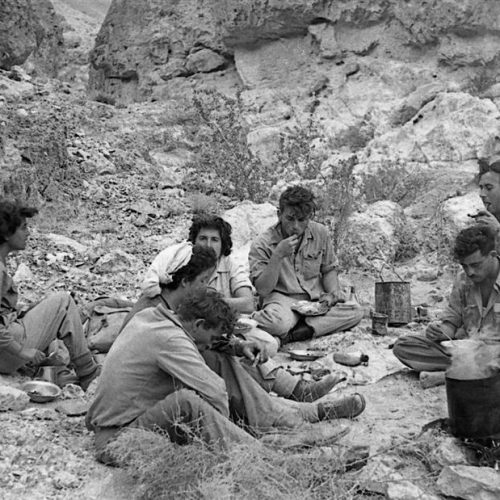

A youth sits before a bisected landscape: expansive and arid, it extends beyond his feet; a group of hikers sits on the edge of the cliff, facing a crater; a long line of tiny figures punctuates the skyline: like a snake, the curvaceous line of hikers casts its shadow on the barren desert landscape.

In Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s famous work, The Monk by the Sea (1809), a small figure stands in a biblical landscape, in a horizontal space of sea and sky, but the latter is so vast that it takes up some three-quarters of the painting. Uncontainable in its infiniteness, the sky highlights the isolation of man and the sublimity of the universe. In comparison to Friedrich’s image of the minuscule monk, the youth sitting on the edge of the cliff in Alon’s photograph radiates the comfort of one who feels at home, and the landscape at his feet becomes a round, embracing sphere, like a huge sandbox, free of threat, devoid of divine revelation, awesome in its splendor, simultaneously containing and contained.

The man hiking in the desert landscape in Alon’s photographs – even in his solitariness within the space – does not radiate loneliness: a community or group to belong to are there somewhere. This comfort with the landscape also hints at an outlook on identity. The befriending of the “primeval landscape” reflects that the hiker has learned the desert way of life, and is acquainted with its hollows, roads, and paths. The desert is not foreign to him and he seeks to make it his landscape. Thus, the concept of identity is something in the spirit of “man is shaped by the mold of his homeland’s landscape.”

Oz Almog notes that the “annual excursion” or the “journey” is intended to strengthen the bond between the native Israeli and his homeland. He emphasizes the term “journey” as compared to “excursion” – the journey is unique in its duration, in the length of its path and the physical effort that is a result of the equipment’s weight, the heat, and water discipline (1). The Israeli nationality is assimilated into the body – according to the contemporary critical approach. strengthening of the body, and group bonding in extreme conditions, for good and for bad, are not the option of choice today, certainly not in mainstream of Israeli society. Despite that, the vitality of the legacy of the journey has not disappeared. The hike on foot with a backpack and walking stick to tour the length and breadth of the land is an experience that instills a social and ethical message – as evidenced by the success of the Israel National Trail project, which has seen families and individuals connect with and introduce themselves to sites that are key to people of spirit and action.

Alon recounts, “When you hike with a group you are not alone, you adjust your pace, so there are no heroes racing forward while the weak lag behind; the procession is unified. Night falls and you begin to gather fuel for a fire, to prepare food together, to set up the campsite, to sit around the campfire, to sing together. It is the act of sitting together around the campfire with coffee and a snack you carried with you that is an experience unlike anything else. It creates a togetherness that is part of forging a society.”

Forging a society is a fundamental of Alon’s world; it is a profound value and not simply rhetoric. In bringing to light the aspect of “togetherness,” his photographs summon up a complex experience. At its base is the relationship between man and the world; as an outcome of that, relationships are also built between men – that is, a society is built.

“Desert, Kibbutz, Nature” – these are not photographs of the sublime desert experience, nor of the magnitude of revelation in the vast expanse. Alon’s photographs are not festive. The secular infiltrates into life matter-of-factly, even in photographs of events and holidays at the kibbutz, and even in the group photos – which answer to the rules and mission of this special genre. The trees are the provinces of memory – they contain the slow movement of the daily process of which they are a part: the small moments, the dust, the mud, the vulnerability in the face of man. There is no idealization in the depiction of kindergarten children in an environment where things are placed randomly among weeds sprouting wild. Kibbutz paths, meanwhile, appear swampy in winter and there is no heroism in a chance meeting on a gray day while scraping the mud off one’s boots.

David Maletz, Alon’s neighbor in Ein Harod, also believes laying a foundation between man and the world, first of all, is the individual’s responsibility – and from it stems the creation of the society as an everyday act:

“This integration of ideal and everyday, in my opinion, adds the flavor to life and the flavor in life. It contains the force of holiness, which is the foundation for creating cultural values, for establishing life patterns. We do not contain within us the power of an absolute decree, but something begins to take shape in the depths of the group that constitutes the source of absolute order.”(2)

Azaria Alon, like David Maletz, believes in a man who was commanded to work and to preserve, not to damage, and has devoted the best of himself and his energy to this. Maletz and Alon acted and created within the same society, and developed complex, dialectic relations with the world, with man, with society. Throughout his life, Alon has opposed the overwhelming, global design trends of “all man” and “all nature.” In the 1950s, for example, he opposed draining Lake Hula to serve agricultural needs. His photographs are characterized by the view of a photographer who has grasped “correct” composition on one hand, but on the other hand also knows how to embrace the coincidental, the intimate, the unexpected, and the faith in the internal logic that flourishes in man and in nature here on the face of the earth, not in the clouds above.