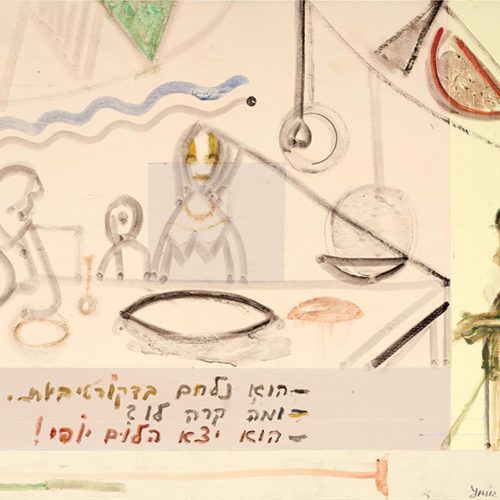

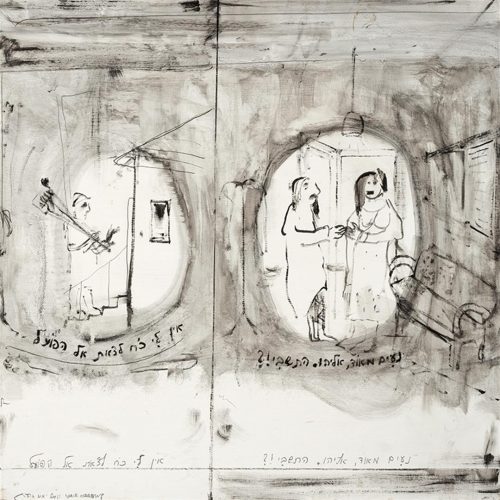

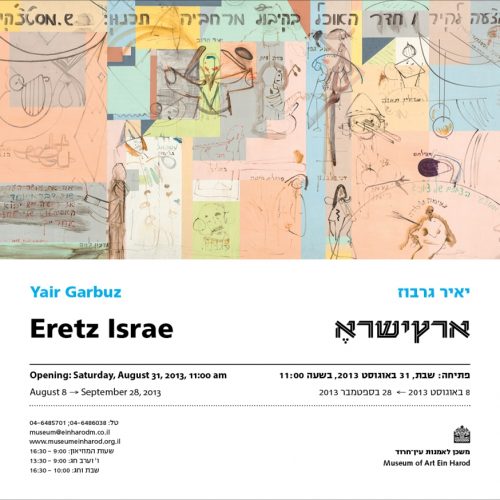

EretzIsrae is the title of Yair Garbuz’ new exhibition and of the book that accompanies it (graphic design: Noam Shechter). In the Hebrew the word “Israel” is truncated, and the vowel sign for a short e (as in “well”) inserted under the final letter instead of the standard vowel sign for the dipthong ai (as in “wail”) indicates a lack of admiration for the way a diasporic idiom is being used in Israel. The exhibition, which includes paintings and reliefs from recent years, is a further stage in the journey of many years and routes that Garbuz has been conducting in his endeavor to sort out the errors made and the successes achieved here in the initial stages. He performs a deconstruction of the Hebrew language and of the ideology of Zionism and of the settlement movement, principally that of the kibbutzim, attempting to understand them by means of disassembly, critique, and shock. These art works have numerous and diverse sources: the design and the graphics that accompanied our movement years in the city or the countryside, the Zionist pathos and the collective culture that were also aided by the well-known slogans that we repeated and sang and declaimed, the local architecture that tried to create Israeli models, the schoolbooks and the guidance and the heritage. Also present here, this time as well, are humoristic visual analyses of Israeli art and yet another thorough clarification of the question of the place and the home, as well as of the difference between the home as a text and the home as a physical entity. The exhibition engages with the past not from a nostalgic perspective that beautifies it and thereby makes it false and useless for arriving at conclusions, but through an investigative gaze which certainly possesses both the strength and the weakness of wisdom after the event. Some of the works were done with a knowledge that the most suitable place for them is the Museum of Art, Ein Harod – because of its distinctive character, but also because of its architecture and because of its location. These are paintings created from a stance that says “Only about myself can I recount”, and they thus constitute a continuation of Garbuz’ engagement with the question of the artist who lives in a province. The paintings are connected with the topography of the place, for a person is closest to himself, and they therefore contain a large degree of genealogy. Without this constituting a contradiction, we can also find European Jewish affinities and associations in them, for these too are channels that have suffered being forgotten and suppressed, trampled by the sweeping Zionist imperative and the endeavor to create a New Jew. The seeming humor and silliness and frivolity are excavation tools that make it possible to conduct this journey.