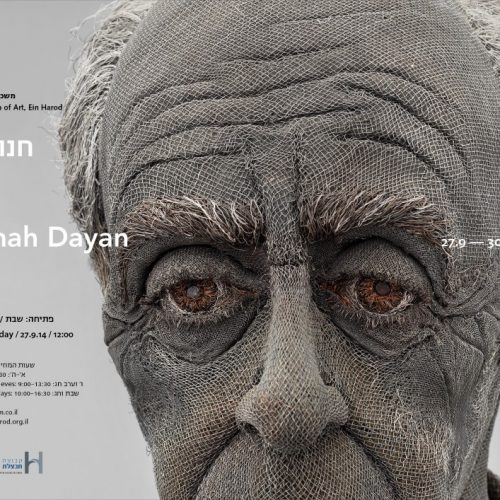

Hannah Dayan creates sculptures in a material that few have made use of in art – wire mesh, a material used in building construction.

Since the early ’90s she has been creating portraits of young and older men and women, mostly of kibbutz members who together with her husband were part of the nucleus of Holocaust survivors who joined the Hashomer Hatzair movement in Hungary and later founded Kibbutz Givat Oz. Hannah Dayan herself is almost 80 now, and remembers nothing of the war years. Her earliest memories begin from her arrival in Kibbutz Hulda in 1943 with a group of the “Children of Teheran”. Theater plays an important part in Hannah Dayan’s work. Her father, Wolf Heiblum, was an actor-member of the “Yung Teater” cooperative in Warsaw. In Israel he Hebraized his name to Zeev, but he was a Yiddishist and remained so after all the horrors of the war. The exhibition catalogue illuminates the connections between her works in iron mesh and the Yiddish theater culture that was an inseparable part of her father’s life, with the world of Yiddish that was suppressed in Israel, and with her early works of dollmaking.

She began working with wire mesh in the early ’70s, when she when she wanted to create large-scale dolls and started looking for a stronger material for their construction. Until then she had used aluminum foil for shaping small-scale dolls. From here on she began using a rough mesh, which had no warmth or softness of its own. Her sculptures are based on cuttings from sheets of mesh that she then sews together with wire, similarly to how such things are done with textiles. In this sense this is “soft sculpture”. While her earlier dolls had a charm of sensuality and gesture and apparent movement in a stage performance, her wire mesh portraits seem to follow the gaze inwards. It would seem that in these portraits one can read biographical aspects, a generation’s travails in life, but a different critical interpretation could also be presented. For example, Haim Maor saw them as “the iron people, the salt of the earth”, and wrote that disappointment and criticism could be seen in their faces. But not all of Dayan’s portraits are of kibbutz members, and some of are of people who were part of her life, sculpted after their death, like the ones of her father or of Oyzer Huldai, a teacher who was the director of the school at Hulda. Most of these sculptures are large, sometimes immense, portraits of heads, hollow, not directly connected to the tradition of the “bust” of art history. A theatrical element seems to reverberate in them, and they conduct us to deep layers in an intimate dialogue that cuts across categories of high and low. And it’s possible that this is also a dialogue with doll art, which never attained its deserved place in this country, and with Polish artists such as Tadeusz Kantor or Jozef Lukomski, who transformed peripheries into a center and in whose work the Jewish theater lives as an open source of inspiration that asks about the “self” that remained behind, in childhood, about the dead in the living and about the living in the dead.