The underlying theme of the exhibition is the role of architecture as an active partner in the shaping of a society and in contributing to the quality of human relationships within it.

Kibbutz planning presents a unique architectural challenge, for the kibbutz is a voluntarily way of life based on equality, mutual aid and full partnership in all the social and economic aspects of life, including property and land. This social ideal, which reformist and utopian architecture sought to promote in various forms from the 19th century onwards, remained mostly in plans on paper. In the kibbutz, in contrast, the collective social vision was from the very outset translated into architectural language and a form of spatial organization.

Since 1910, 280 kibbutzim have been established in the semi-desert Negev, in the hill country, on the coastal plain, and were joined by immigrants from diverse countries of origin. Kibbutz architects have been asked to provide specific answers for diverse hues of social relationships, which have found expression in distinctive versions of overall settlement planning, of the connection with the landscape, of the placement and design of the public buildings, the residential and the production zones, and of the relations among them.

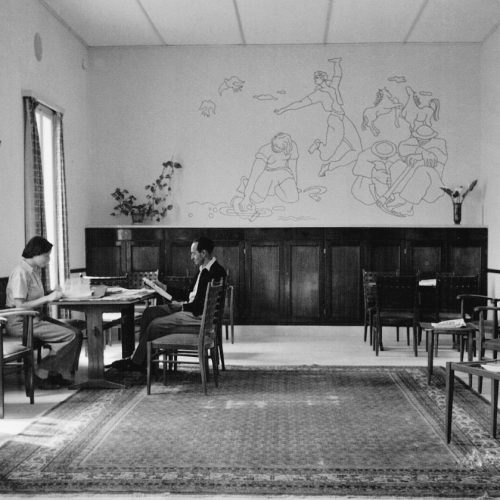

The kibbutz is a single undivided space, throughout which many daily functions usually associated with the domestic sphere are dispersed, and in which there are no fences or private plots. It contains all the dimensions of life and is collectively owned by all the members. The focus of social interaction in a kibbutz is the large central lawn with the public facilities, the dining hall, and the culture house situated around it like a “forum” or “agora”. The undivided yet complex character of the kibbutz architectural space facilitates its adaptability to new demands arising from orientations of change.

In recent years many kibbutzim have been undergoing a radical shift: a transition from a socialist conception of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” to the principle of differential earnings linked to the rules of the market, although the “safety-net” still subsidizes education and health as well as social security and mutual aid on a scale unknown in other forms of life. With regard to architecture, many kibbutzim are today experimenting with varying degrees of privatization of the collective kibbutz space, and its unique fabric is in danger of destruction. Nonetheless, in the past three years there has been a discernible wave of return to the kibbutz, as well as a rethinking of its architectural, environmental and spatial values, and a developing of new and original models of solidarity and mutual aid.

Will we be able to think about the kibbutz not merely as a social experiment that has exhausted its potential but as a proposal for a very contemporary discourse, as a kind of local “Welfare Community” structure that offers an alternative – on the one hand to the nation-state that is providing fewer and fewer welfare services and, on the other, to the generic-spatial default option of the separatist suburban model? Is there a chance that the discussion about the transformation of the kibbutz and about new forms of organization of mutual aid could extend to beyond its Zionist origins and consequently generate new structures, new spatial relationships unknown to us as yet, and a pertinent dialogue between architecture and society?

The Israeli pavilion, Venice Biennale 2010

Kibbutz – Architecture without Precedents

Curators: Yuval Yaski & Galia Bar Or

January-April 2011