Dan Frank did not belong to any of the major styles of Israeli art, which may account for the reason he staged relatively few exhibitions outside of his kibbutz. However, he was alert to his environment, involved and greatly concerned with the kibbutz and its destiny. As an artist, he expressed what it was like for the second generation of Kibbutz members, who were born into their pioneer parents’ idealized vision and then witnessed it change as they entered adulthood. Only during the last two decades of his life, after he moved to New York and returned to his kibbutz, could he bring himself to openly protest, both in his works and his writings:

“I would perhaps like to talk today about art and the kibbutz in terms of their mutual idealization: Of a splendid combination, but reality is not so. Not that there is no creation here, God forbid. They have created a beautiful farm and kibbutz; created a fantastic place. However, artistic creation, the artist and society as a whole are vectors that push up against the creation called the kibbutz, or they have no vector at all. Artistic creation is part of the society, and thus – they lag a generation behind the collective economic creation. Something disturbed the development of the artist / art on the kibbutz.”¹

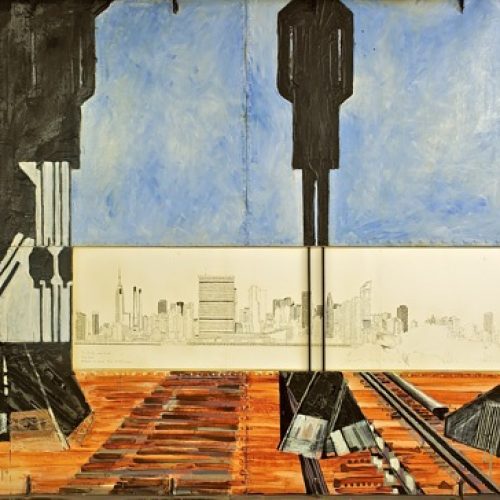

His complex relationship with the kibbutz set his path as an artist: It promoted him and held him back at the same time. Popular and valued for his talents, he was often in anguish and frustrated with the difficult working conditions for creation and creativity. In the early 1950s, art was seen in the kibbutz as a hobby, not a profession. Therefore, the scarce amount of time that Frank had for his art was after work, in his spare time. After graduating from Oranim and the Avni Institute, he was sent by the kibbutz to study something more useful than painting – industrial design at the Technion –, so that he could contribute his skills to designing and planning on the Kibbutz. During the time that he worked in the technical department of HaKibbutz HaArtzi in Tel Aviv, he improved his sketching and drawing abilities and developed his architectural style, however, he spent his days working, therefore, his meticulous sketches were created when he was on vacation and visiting various cities in Israel and abroad. His drawings from this period display his search for structure and rhythm that characterized his earlier works. Generally speaking, we can say that his paintings from his first two decades of work remained within the safe zone of landscapes and still life. Falling ill with cancer in the late 1970s was for him an intense experience that pushed Frank beyond the limits of the familiar. His desire for personal freedom as an artist and from the kibbutz, led him to move to New York for two years in 1986-87.

After returning to the kibbutz and studying under Doron Bar-Adon, Frank’s works displayed a disillusionment from the innocence that characterized his early paintings. In the 1990s he began to create in a very expressive style, large dimensional works that reveal anxiety, loneliness and pain. He was attracted to the boundaries and wanted to shock the social norms in the Kibbutz society. He chose themes and styles totally different from each other: from blatant pop erotica in light blues and pinks to roughly splattered black paint in his paintings of locomotives and airplanes.

In the series, “the dog adheres to his master’s voice”, he expresses blatant criticism of the kibbutz society in a symbolic and expressive manner alike. The Bulldog tries to guard the lost herd, but both his and the herd’s obedience and loyalty prevent them from a real search of the way. At this stage of artistic maturity, he combines a variety of materials and techniques to represent significant ideas. On the one hand, he paints with strong emotions and colors, while on the other hand he uses readymade objects alongside duplication and quotation. This highlights influences from conceptual and post-modern approaches as well as the underlying duality in the perception of the role of an artist in the kibbutz as a producer-creator; as a free individual, versus an individual living in an egalitarian society and expressing its values. During this period, Frank wrote his thoughts about the reasons for the lack of innovative art on the kibbutz:

“I believe that collective thinking was the virus that caused this disability. There is nothing less fertile than a social collectivist approach, as necessary as it was […] and still is. Not only did it strangle the art, it led us to the place we are at today: a vessel empty of cultural and social creativity, with vague political views and confused social norms, where is the education? ect … this idealistic collective, this flock, that sees everyone as one, with the same orientation and more, when it is dictated from above, how can there be fertility? “For something to be born, there must be at least two different sources – male and female – at least two different thoughts. This is a society that has suppressed new ideas and thoughts, and art is the first to suffer…

Apparently, a totalitarian society cannot tolerate any exceptional members, and this is the result: a lack of social creation, including our shallow art. Meanwhile we move on the inertia of ‘scorched earth’ that was left behind by the collectivist/social concept, but if we seriously look at the causes, we may also be able to change the result.”²

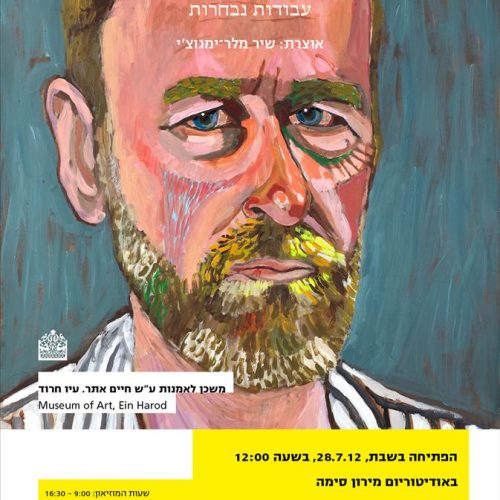

These words clearly express Frank’s personality: direct, true to his conscience and his role as an artist – to look around with open and sober eyes. In his final years, he became increasingly ill and he lost his strength. A series of large plywood boards remain waiting for him in his studio.