The book and the exhibition The First Decade, A Hegemony and a Plurality at the Museum of Art, Ein Harod propose a layered view of the visual art created during the State of Israel’s first decade (1948-1958). Chronologically, this is the first portion of a joint project by six museums in this country – a series of exhibitions on Israeli art, divided by decades, to mark the state’s sixtieth

anniversary.

On the face of it, the division by decades forces an arbitrary constraint of historical periodization, connecting a foreign meaning to deep processes that are by their nature dynamic and long-term. In our case, however, this division made it possible to deviate from the prevalent framework of a narrative that crosses decades – the familiar hegemonic narrative, which became established in the first decade and described the history of Israeli art as a “progress” towards a distilled modernist utterance. It seems now that the synchronic focus on a single decade has enabled us to actually explore the lateral plurality, the diversity of orientations that were suppressed, ignored or forgotten in the teleological trajectory which became enshrined in the Israeli art discourse. The central place in this narrative was taken by the “New Horizons” group, which was founded in 1948 and attained to an influential position for several decades; the synchronic perspective, however, illuminates not one exclusive position but a network of reciprocal relations, orientations that took shape in relation to one another as an inseparable part of a rich and diverse cultural complex.

Moreover, it appears that the project organizers’ avoidance of any thematic framework reflects the need to once again anchor the expressions of art in their historical time and place.

The state’s first decade began with the United Nations resolution to partition the country, the Declaration of the State, the invasion by the Arab states (Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon) and the war that “was the heaviest in the number of casualties the State of Israel has known”, while those who paid with their lives were mainly members of the young generation that had reached adulthood in that period. This war, our “War of Liberation”, became inscribed on the Palestinian side as a trauma, a catastrophe (“the Nakba”): some 400 Arab villages and urban areas were destroyed, some 600,000 Arab residents became refugees. There is no way to embrace, here, the expressions of longing and suffering and idealization of the homeland in the works of Palestinian artists who were active in exile in the ’50s. These works are not being shown here, but their story is an inseparable part of this place’s memory and a living foundation in the contemporary confrontation with the picture of the future.

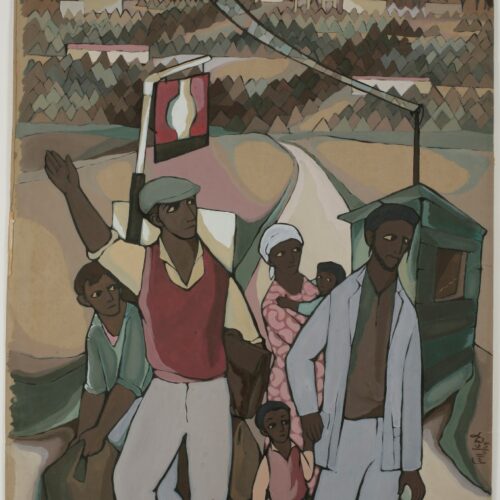

The first decade was a period of mass immigration, of Holocaust survivors from Europe and Jews from Arab states, which tripled the Jewish population in this country. It was a time of confrontations with change, distress and conflicts, a decade of sweeping and resolute state centralization, shaping a collective-national “Israeli” identity. Early in the decade (on 15 January 1949), David Ben-Gurion defined the period’s challenges:

We are bringing to this country a unique nation, one dispersed in all the ends of the earth, that speaks many languages, has been educated in foreign cultures, is separated into various tribes and groupings in Israel. This multitudinous and many-spotted public it is our task to fuse anew, to pour into a mold of a renewed nation. We have to tear up the partitions of geography, culture, society and language between the various parts and to pass on to them one language, one culture, one citizenship, one loyalty, new laws and new sentences. […] At the same time we have to look after their security, the security of the state, its liberty and its place in the world. And we have to do this work in a period that is stormy and full of disputes, when the world’s peace is hanging on a hair and we are surrounded by enemies.

On the one hand, the resolute channeling of the state to a centralized governance (the “Altalena” affair) nipped anarchic tendencies in the bud, but the imposition of a single picture of the future – social, economic and political – pushed to the sidelines alternative currents that enriched the society with diversity, layering and depth. Even within the workers’ movement, which encompassed a range of social visions and approaches and was split into separate educational streams and independent cultural frameworks, this orientation of the governing power to make everyone bend to the authority of the state mechanism was discernible. In those years a collective memory was shaped in the spirit of the Ben-Gurionic shaking-off of diasporic-Jewish characteristics, but nonetheless channels were found for expression in Yiddish, for exhibiting Jewish art from the diaspora, and for commemoration of the Holocaust, and these seeped like underground streams of psychic layers through the art of the period. It is impossible to understand the plurality revealed here in the art of the period without a profound confrontation with the ethoses and the specific social conditions that constituted its substrate.

Moreover, a gaze at the rich fabric of the first decade cannot ignore the infrastructure that was laid down here decades earlier by the “old Yishuv” and the Sephardi communities that made up its majority. As a continuation of this, in the 1920s and 1930s an extensive social, cultural and political network was built here by the Eretz-Israeli workers movement, a blueprint was drawn up for the future society, and its characteristics and its tools were shaped in the light of alternative social visions. These embraced a diversity of positions that defined different relationships in the society, including a place and a function for art, the artist, and the individual. The workers movement, with its various currents, promoted the creation and diffusion of modern art “for the people and by the people”, and on this background in the ’50s there already was in Israel an extensive institutional network of culture and art, in the center and in the peripheries (the building of the Museum of Art, Ein Harod, the third museum in this country, exemplifies this well).

The title “A Hegemony and a Plurality”, used to describe a decade rich in events, charged with conflicts and suffused with nation-building endeavors, hints at a revision – a conscious choice to expose the repressed and hidden critical and alternative dimensions that pulsed at the margins of the cultural system in the ’50s. Such exposure of the “plurality” seeks to create a balance, to challenge the consensus and perhaps even to undermine it by showing alternative elements. True, the hegemonic narrative of the time has already retreated from the forefront of the stage, and today, in the early 21st century, the glamour of “New Horizons” and its work to advance modern art have already dimmed. But on the background of the upheavals of the times and the shattering of hierarchies, we still need to ask what the meaning of the “plurality” exposed here is: do the repressed, the hidden, the critical, the alternative of that time still retain, today, their fertilizing status as vital elements in the cultural system? Do they have the capacity to arouse intellectual, political, and cultural tension – or will they be dropped indiscriminately into a consolatory slumber of collective nostalgia? What relevance is there in presenting an exhibition, and in critical activity, in an era “without values”, an era that no longer aspires to social agendas?

We have curated “The First Decade, A Hegemony and a Plurality” with the wish that the encounter with the art of the period will be experienced as a fresh and topical experience, and that the view it offers of the past will show a picture of a charged and challenging socio-cultural fabric – not as a description of something missed out on, and not as an idealization, but as a meaningful source of inspiration that arouses the imagination to a different possibility, to contemplating the past from a perspective of a future.