Bonsai: The Cedar, the Shittah Tree, and the Myrtle, and the Oil Tree

It is disconcerting to plant in bonsai – the Japanese art of dwarfing and shaping plants – the cedar, the shittah tree (acacia), the myrtle, and the oil tree, or to set in a handful of earth, within a stylized container, the fir tree, and the pine, and the box tree, but not together. The hybrid generated by the crossing of two lingual and cultural structures – Eretz-Israeli flora and a Japanese miniature imitation of nature – shakes the viewer like a hybrid product that causes a troubling, thought-provoking, aesthetic disruption.

Bonsai culture does not reflect an attraction to the abnormal (whether the midget or the monster) as a manifestation of nature’s creativity. Quite the opposite: bonsai is not a genetic mutation but rather man-made; it displays a personal aesthetic sensitivity via a manipulation of nature which is a displacement and miniaturized imitation of a picture of the world. Bonsai is a semio-phorus (carrying meaning) art object, intended to be viewed in a designated display space, within a niche or an architectural enclave, at home rather than in a museum. Bonsai is an object of intimate observation from a single, specific angle, and is meant to be observed only.

The four species, a selection of indigenous Eretz-Israeli plants presented in the sukkah during the Feast of Tabernacles, are an authentic part that represents the whole in nature. The fruit or branch is not a miniaturized copy of nature, but rather a projection of the tree from which it was taken. The four species are not a mere object of observation; they have a function in a ritual, setting the various senses in motion and instantly triggering a linguistic-cultural memory of a homeland, the taste and scent of a plant, with its roots, branches, fruit, the soil in which it is planted, the landscape’s history, climate, and images. The whole demands the validity of the part (the fruit or the branch), a flawless validity, wholly intact. The tree’s branches have not been broken off, its leaves have not been torn off, its fruit has not split, and its stalk has not been lost.

Bonsai is not a part of a whole. It is an entity that functions as an independent system, being detached from the ground. It is a natural-artificial microcosm shaped through random restriction of growth by wiring branches, twisting, trimming, truncating, wounding, uprooting, root pruning, under-fertilization and underfeeding. Bonsai is based on strict rules of re-shaping nature. The artist has unshakable control of this microcosm, but at the same time, this human intervention is indiscernible, and the bonsai appears natural and harmonious.

In both cultures, the Jewish and the Japanese, ancient times are revered as part of the structuring of a collective identity, emphasizing a generations-long tradition that has been assimilated over the centuries. One of the categories for the evaluation of bonsai is its antiquity: at times the bonsai has a life span of generations, and it is passed on in the family, venerated for its longevity and on account of the memory of the ancestors who nurtured it.

The image of Eretz-Israeli plants, albeit forever fresh, in fact looks back, to a time and place embedded in the past. Eretz-Israeli plants call to mind a land of the patriarchs, where they have grown and flourished since the beginning of time, as it were. They are the gift of the Creator himself, “a land of oil olive and honey,” long before the people’s exile from their country. Through their natural growth, their rooted qualities, and the stylized identity, they tie the eternal triad of flora, man, and land together with memory threads. Their image embeds a physical, emotional and spiritual memory of love and courtship, love of the people of Israel, love of the Shekhinah (Divine presence), and love of the land: “This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes. I said, I will go up to the palm tree, I will take hold of the boughs thereof” (Song of Songs 7: 7-8).

Unlike the bonsai, the habitat of Eretz-Israeli plants, namely the land itself, cannot be transported to the Diaspora. The hands embrace a citron or a palm branch carefully packed after a long, tiring journey from the end of the East to the end of the West, causing the heart to tremble with yearning: “Have you known the land/ Where the pomegranate blossoms/ And the citrus between the branch foliage/ Shimmers.” (Pampinsky, “Zion’s Violin”)

The image of the plant turns to the future, to a vision of national independence, of redemption and the end of days, of a people dwelling in its land. The plant’s aroma and taste have not dissipated; they inundate every festive day, every prayer, legend and midrash, bearing a promise for a better future: “And all the trees of the field shall clap their hands. Instead of the thorn shall come up the fir tree, and instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle tree” (Isaiah 55:12-13).

Israel’s plants are perceived as an integral part of the Land of Israel, whereas the bonsai was imported to Japan with the expansion of Zen Buddhism and in the wake of the wave of cultural influence from China (in the 12th century). Observation of the bonsai is oriented toward universal spiritual truths, alluding to natural scenes. Twin trunk, for example, may recall the affinity between the male and the female elements; a combination of several trees – the relationships between an individual and a group (family), man and universe, or a dragon climbing up toward the sky. At the center, which is never inhabited by the plant, a place is preserved for the encounter between heaven and earth, divinity and man.

Due to its universal context, the bonsai does not deny Eretz-Israeli plants, as long as the formal-artistic effect is maintained in its structure: the correct placement of the plant within the container, its proportions and style. Eretz-Israeli plants, on the other hand, deny bonsai, the miniaturized entity that subsists independently, dissociated from the ground, an entity that undermines their very existence as a cultural image and disrupts the set of mutual links which is their very essence: their formative affinity with the land, their functional mutual link with man (shade, fruit, roofing, fibers, beams), and the reference to God as the Creator who furnishes them with meaning and historical function.

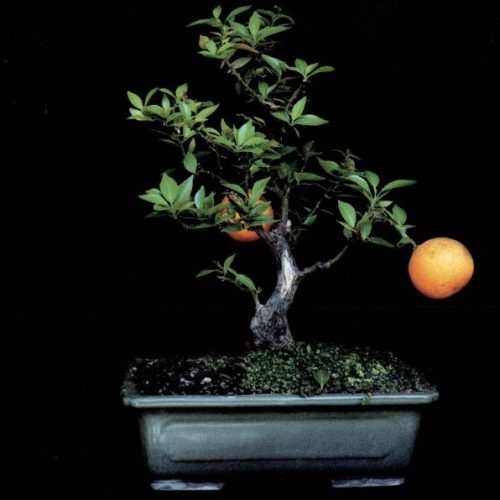

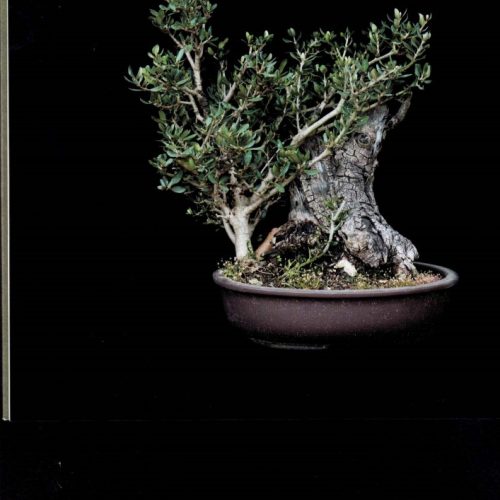

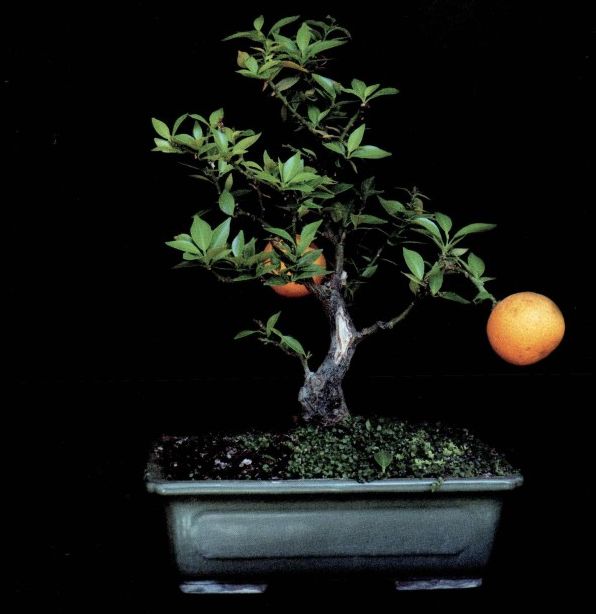

Yehudit Matzkel’s photographs reinforce the gap between the organic “Israeli” image of Eretz-Israeli plants and the sterility of the bonsai through meticulous camera work. The photograph accentuates the detachment from its natural setting through the choice of a shooting location, a neutral studio space rather than the bonsai’s growing site, a greenhouse or the open air. Matzkel opts for a specific type of photography, with its own context and language, a style of portrait photographs taken in a professional studio: the subject stands with his back against a black backdrop, and is shot with frontal lighting.

Another important aspect is the works’ mode of presentation in the exhibition as well as the catalogue. Matzkel juxtaposes two disparate structures, textual (words) and iconic (image), whose combination generates a new system. On the one hand – the name of the plant in the biblical sources, on the other – its photograph in bonsai form. Thus, for example, the text acquires a denotative value by indicating that this tree is a fig. In order to believe the text, the viewer must first relinquish his inner world, his ethos, sentiments, language and culture. He must push back the cultural image of the tree, which contains the dimensional proportions with the person finding shelter under it, an important quality in a culture spun under conditions of burning sun. A verse such as “every man under his vine and under his fig tree,” (1 Kings, 5:5), for example, sounds grotesque in view of the dwarfed fig in the bonsai photograph.

Yehudit Matzkel does not call to abandon an ethos or a sentiment, and the critical context arising from her work is stratified. The jolt caused by a paradox such as the cedar of Lebanon that has flourished in bonsai to the height of a mere few centimeters, is thought-provoking precisely due to the insight that the viewer is unwilling to yield the plant’s stable place in his cultural world. This jolt confronts the viewer with questions pertaining to the very essence of the ostensibly self-evident affinity with Eretz-Israeli plants, presenting a quandary about its modes of structuring as a collective cultural identity with an agenda all its own. On another level, the question arises, whether there is any connection between the affinity with nature fostered for centuries in the Diaspora, and the preservation of nature as an everyday consciousness of the people living in Zion. Is there a link between the images of nature in the context of a Biblical past, its images as a future in the vision of the end of days, and the image it is given in the present, in a concrete setting strewn with conflicts, destruction, tree uprooting for nationalistic and political reasons, pollution, artificial gardening and sterile landscaping in the public domain, and construction oblivious of the landscape?

The local-national context of the Israeli plant incorporates the universal context that indicates the affinity between inter-personal relations and the evolving relationship between man and nature: “and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks; nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. But they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree; and none shall make them afraid;” (Micah 4: 3-4).

Yehudit Matzkel

Tree of Life, Photographs

Curators: Dalia Levin, Galia Bar Or

June-September 2005