One can begin describing Hanna Farah’s exhibition at the Museum of Art, Ein Harod, from its title and through three prisms—Farah has given it three names that enable it to be seen from a multiplicity of viewpoints, a name of its own in each language. “Foot Notes” (in English) emphasizes its partial, fragmented, processual and inwardly oriented aspect, as opposed to the representational aspect of a closed an Takhbutat”, “ ,” تخبطات“ ; d summational narrative (“beating one’s brain” in Arabic) focuses on the inner movement of doubt, intensified by this word’s root that evokes a pounding / a blow / a shock—the body’s memory absorbed into a depth-experience that seeps into the Khashashot”, (“fears” in Hebrew), a “ ,”חששות“ ; language word that comprises a doubling, the khash (“[he] sensed”) has become khashash (“[he] feared”), and the word’s sound (onomatopoeia) hushes—or warns.

Farah’s work is very structured, but it allows interpretative freedom. The physical and the sonic form an inseparable part of the conceptual and the emotional, and it is probably not going too far to associate the word khashash with, for example, the word khatzatz (“[he] divided”; also: “gravel”), and to reflect on the element of division and partitioning present in both words and also on how gravel, as a surface in its compressed transformation into a floor-tile (a balata [an Arabic word that has been absorbed into Israeli Hebrew (Tr.)]), is an integral part of this exhibition’s context.

Each of the three titles stands for itself in its language, and is no way subservient to direct translation. Each has an intimate character, something diaristic—confessing, commenting or reporting—and is expressed in the present tense, the time of the writing.

Hanna Farah is exhibiting photographs. He photographed the earliest of them during the first years of this century, and some of them have been exhibited before in other frameworks. The photographs have accumulated over the years and have become an active archive or a living diary.

The name “Foot Notes” directs one’s gaze towards the bottom margin of a page of text, but also to what exists underfoot. Many of Farah’s photographs tend to dive down towards the ground’s surface or even lower than that, to the layer beneath the laid tiling of the surface. Farah—an artist who is well versed in building practices—incorporates in his works codes from this trade as well as concrete and metaphoric contexts—extricating a tile by cutting a cross pattern, engaging with the exposing of substrates, with building techniques and wrecking techniques, or, in the broader metaphoric sense, with the concept of the house or home.

This directing of the gaze towards the observer’s feet was present in his early work. The gaze dives downwards, looking for the place from which information and material has been taken (the footnote), which also contains what has been omitted from the central narrative—the contents of the concealed, of the non-explicit, or of what evades an agreed logical sequencing.

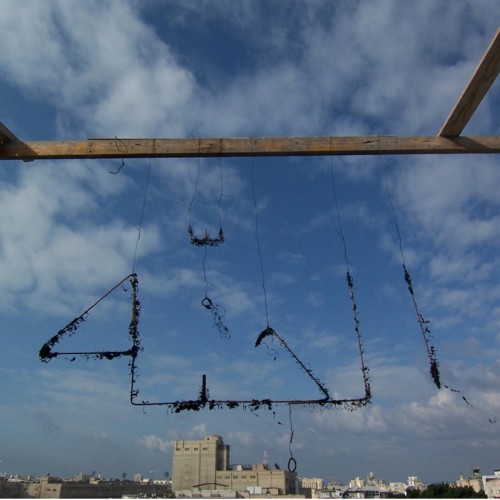

A few of Hanna Farah’s photographs do turn a diving gaze upwards, to the infinity of the upper expanse, to what takes off as a kind of promise or threat, gets dizzy or hovers, demanding its return as a phantom.

In later photographs the point of view embraces an interior or exterior expanse from a horizontal angle that registers a horizon line, or from an oblique angle that registers the most encompassing surface possible of an object or an expanse—a photograph that seems to make use of the genre of police or catalogue photography.

Farah reactivates these gazes by bringing together photographs of different kinds and from different times, in intersections of languages and in unusual juxtapositions, each of which sets off a new set of emotional, poetic and political reflections. He arranges relations among the photographs—pairs, trios, singles—and positions them beside one another differently and anew each time, like a crossword that has not been completed and never will be. With its controlled aesthetics, his work does not break the rules but it does cut across categories, undermining boundaries of media, of body work and installation genres, of conceptual documentation and of photography per se.

There are 91 photographs in the catalogue and in the exhibition at the Museum of Art, Ein Harod. Some of these have been shown in the past in a different selection or in a series whose title evoked a context relevant to a curator or to the time. For example, the series titled in Arabic ,”משובשים“ Mashuashe” (“Confused”); in Hebrew “ ,”مشوّشة“ “Meshubashim” (“Impaired”); and in English “Distorted” (2005), which Tal Ben Zvi interpreted as engaging with “a biography of the place as a displaced, dissociated, distorted and impaired narrative”.1 Another series was shown under Pituakh shetakh” (“Area “ ,”פיתוח שטח“ the Hebrew title Development”) (2007), which in the (Hebrew) terminology of the building industry refers to the excavation work done to install the plumbing, sewage and communications infrastructure.2 Other works were shown in an exhibition titled in English “Re: Form, A Model” (2010),3 which focused on the village of Kufr Bir’im and gave expression to the utopian dimension in Farah’s work and world.

Farah’s full name is Hanna Farah Kufr Bir’im: it was his choice to connect his identity inseparably in this way with the village where his family, his parents and his grandparents were born, the village whose inhabitants have not been permitted to return to by the Israeli authorities for more than sixty years. For Farah the village of Bir’im is a foundation experience: “Not infrequently I begin with the form of a simple cube that reminds me of my grandfather’s house.”

While it is a foundation experience in Farah’s biography, in the field of representations in Israel Kufr Bir’im is a blind spot, a present absence that continues to exist as an inseparable part of the identity of everyone who is a participant in the life of this country. The containing of memory and the taking of responsibility are conditions for making life possible, conditions for agreement. Yet Hanna Farah’s work offers a multiplicity of points of view, not a manifesto. The gaze that dives downwards or upwards or at an angle seems to expose the marginal, not the dramatic—the tension that is built up by the small moments, not the history of the big events: something has happened or will happen here, see, twigs have been torn off, stubble has been trampled, these are traces, and even an improvised fence designates something. Other photographs: a close up of a lily in full bloom, a sabra cactus and a nettle, a poignant beauty and a feeling of marveling but also a testimony and a symbol, a still-life, a run-over cat, a wound, remnants of a body, remnants of a house and also a separation wall, an exterior that has seeped into the interior and been turned inside out.

“To lose the body’s lines is to lose its boundaries”, Hanna Farah Kufr Bir’im has noted. This exhibition (if we translate all its titles into English), is called “Foot Notes— Beating One’s Brain—Fears”, and it is tuned to a low frequency that is sensitive to the fabric, the fabric that absorbs all the signs of violence, that is being woven all the time—the fabric of life here. In Farah’s work there is no nostalgia and nothing elegiac; the controlled, quasiformalistic aesthetic, with its non-hierarchic method of sorting, binds together stills from a video with a diversity of photographs, the low bound together with the high, the high with the low, the object with the subject and the inanimate with the living and with the body. Independent in their own way, they connect with one another, like units of memory that carry a code for deciphering, in a temporary structure of “present time”—a structure that is temporary in its fragile but imperishable uniqueness.

اسمٌ خاصٌّ به غاليا بار أور

يُمكننا البدء بوصف معرض حنّا فرح في «مشكان لأومانوت عين

حارود » المشار إليه في العنوان، من خلال ثلاثة موشورات: لقد أعطاه

فرح ثلاثة عناوين، وهو ينعكس بتعدّد وجهات النظر، فلديه اسم بكلّ

لغة: “ Foot Notes ”، هوامش بالإنجليزيّة، وهو اسم يشدّد على البُعد

السيروريّ، المتقطّع والجزئيّ، المُوجّه إلى الداخل، في مواجهة جانب

التمثيل لسرديّة تلخيصيّة ومُقفلة؛ «تخبّطات »، بالعربيّة، وهو تعبير

يتمحور في حركة داخليّة من الشكّ، تتعزّز بفعل الجذر خبط-ضرب،

حيث أنّ ذاكرة الجسد مُرسّخة في تجربة عميقة تتسرّب إلى اللغة؛

و”חששות”، مخاوف بالعبريّة، وهي كلمة مؤلّفة من إدغام يحوّل المعنى

من «أحسّ » إلى «خشي »، والمحاكاة اللغويّة تُسكِت أو تنذر.

إنّ عمل فرح شديد الإحكام، ومع ذلك فهو يتيح حريّة تأويليّة.

فالماديّ والنغَميّ هما جزءٌ لا يتجزّأ من النفسيّ والمفهوميّ، ويبدو أنّه

لن يكون من باب المُبالغة الذهاب حدّ ربط كلمة «خشي » بلفظها العبريّ

)حشاش( بكلمة «حصى » )حتساس(، مثلاً، والتمعّن في أساس التفكيك

والصّقل الكامن في كلتيهما، والصورة التي يشكّل فيها الحصى كمسطّح،

وبصيغته المضغوطة كبلاطة، جزءًا جوهريًّا من سياق المعرض.

إنّ كلّ واحد من العناوين قائمٌ بحدّ ذاته في اللغة التي صِيغ بها، وهو

متحرّر من الخضوع لترجمة مباشرة. لثلاثتها طابعٌ حميميٌّ، يوميّاتيٌّ،

مُعترِفٌ، يُدلي بملاحظة أو تقرير، وزمنها هو الحاضر، زمن الكتابة.

يعرض حنّا فرح صورًا. قام بالتقاط الأقدم من بينها مطلع سنوات

ال 2000 ، وعُرِض قسمٌ منها في الماضي ضمن أطرٍ أخرى. وتراكمت

الصور بمرور السنين لتصبح أرشيفًا ناشطًا أو مفكِّرة حيّة.

إنّ مصطلح «هوامش » هو اسمٌ على مسمّى، وهو يُوجّه النظر نحو

هوامش صفحة النصّ. الكثير من صور فرح تكرّس نفسَها للغوص إلى

سطح الأرض أو ما تحته أيضًا، نحو مسطّح يقع تحت السطح المرصوف

بشكل راسخ. إنّ فرح، وهو فنّان متمرّس في أصول فنّ البناء، يرسّخ

في عمله شيفرات من مجال هذه المهنة ويدمج سياقات عينيّة واستعاريّة:

خلع بلاطة عبر حفر شارة صليب، العمل على كشف بُنى تحتيّة، تقنيّات

بناء وهدم أو – بالمعنى الاستعاريّ الأوسع – تناوُل مفهوم البيت.

كانت حاضرةً في أعمال فرح الأولى وجهة النظر نحو قدميّ

المُتأمّل. تلك النظرة التي تغوص إلى الأسفل وتتقصّى أثر المكان الذي

أخذت منه المادّة والمعلومة، وهكذا يقوم باحتواء ما تسرّب خارج

السرديّة المركزيّة، المضمون الخفيّ، غير المشروح أو الذي انحرفَ

عن استمراريّة منطقيّة متّفق عليها. بعض الصور يصحبُ الأنظار نحو

الأعلى بالذات، نحو لا نهائيّة الفضاء العالي، إلى ما يرتفعُ عاليًا، كنوعٍ

من الوعد أو التهديد، يترنّح دائريًّا أو يُحلّق، يُطالب بعودته على هيئة

شبح.

أمّا في الصّور المُلتقطة في وقتٍ لاحقٍ أكثر، فإنّ وجهة النظر تحيط

بحيّز خارجيّ أو بحيّز داخليّ برؤية أفقيّة، تقتنص خطّ أفقٍ، أو بزاوية

مائلة قُطريًّا، تلتقط سطح الأشياء المحيط بأكثر ما يمكن من الموضوع

أو الحيّز – صورة تقوم كما يبدو باستخدام جانر التصوير الكتالوغيّ أو

البوليسيّ.

يقوم فرح بإعادة تفعيل من خلال ملاقاة صور من أزمنة مختلفة ومن

أنواع مختلفة بعضها ببعض، إجراء تصالب بين لغات عدّة وموضعة

غير معهودة، تحرّك في كل مرّة منظومة شعوريّة، شاعريّة وسياسيّة

جديدة. إنّه يقوم بمزاوجة بين الصّور، أزواجًا وثلاثًا وأفرادًا، الواحد إلى

جانب الآخر، مرّة أخرى ومجدّدا، ككلمات متقاطعة لم تكتمل ولن تكتمل.

لا يكسر عمله الركائز بجماليّته المُحكمة، لكنّه يتجاوز الخانات، يقوّض

حدود الوسائط، عمل جسدٍ وإنشاء معًا، توثيق مفهوميّ وتصوير مُجرّد.

يضمّ معرض وكتالوغ العمل في “متحف الفنون عين حارود” 91

صورة. قسمٌ منها سبقَ عرضه في الماضي، بتجميع آخر، أو بسلسلة

جسّدت سياقًا ذا صلة لقيّمة المعرض أو للزمن. فمثلا، سلسلة «مشوَّشة »

( 2005 )، السلسلة التي فسّرتها طال بن تسفي على أنّها تتناول «سيرة

المكان كرواية مشوّشة، مغلوطة، مقتلعة ومحرّفة 1.» هناك سلسلة

أخرى تمّ عرضها تحت عنوان «وشم (2007) » ، وهو تعبير يعني بلغة

البناء عمليّة حفر لطمّ شبكات مواسير واتصالات. 2 هناك أعمال أخرى

عرضت في معرض «موديل للتصليح (2010) » ، وتمحور حول قرية

كفربرعم، وهو معرض عبّر عن البُعد المثاليّ في عمل فرح وعالمه.

«حنّا فرح كفربرعم » هو اسم فرح الكامل. هكذا اختار وهكذا

بالتالي يربط هويته بشكل غير قابل للفصل بقرية ومسقط رأس عائلته،

والديه وأجداده، قرية منعت سلطات إسرائيل العودة إليها منذ ما يزيد عن

ستين عامًا. إنّ قرية كفربرعم هي تجربة أساس: «يحدث مرارًا أنني أبدأ

بصورة مكعّب بسيط، يذكّر ببيت جدّي

لكون قرية كفربرعم هي تجربة أساس في سيرة حياة فرح، فإنّها

تشكّل نقطة عمياء في حيّز التمثيل الإسرائيليّ، غائبة-حاضرة، تواصل

الوجود كجزء لا يتجزّأ من كلّ شريك في الحياة هنا. إنّ احتواء الذاكرة

وتحمّل المسؤوليّة هما شرطٌ لإمكانيّة العيش، شرطٌ للموافقة. إلا أنّ عمل

حنّا فرح يقترح تعدّدا لوجهات النظر، وليس بيانًا. يبدو أنّ النظرة التي

تغوص عميقًا إلى الأسفل أو إلى الأعلى أو بشكل قطريّ تكشف الهامشيّ،

وليس الدراميّ بالذات؛ التوتّر الذي تراكمه اللحظات الصغيرة، وليس

تاريخ الأحداث الكبرى: شيء حدث هنا أو سيحدث؛ أغصان قد اقتلعت

وقشّ قد تكسّر تحت الأقدام؛ آثار خطى، وكذلك جدار عشوائيّ يشير إلى

شيء ما. وصور إضافيّة: صورة قريبة لسوسنة مزهرة، صبر وقرّاص،

جمال يخزّ القلب، شعور بالدهشة وكذلك شهادة ورمز، طبيعة صامتة،

قطّ مدهوس، جرح، بقايا جسد، بقايا بيت وكذلك جدار عازل؛ خارج

تسرّب إلى الداخل وانقلب رأسًا على عقب.

«فقدان ملامح الجسد هو فقدان حدوده »، يشير حنّا فرح كفربرعم.

إنّ المعرض بمثابة هوامش-تخبّطات-خشية. إنّه موجّه إلى ذبذبة

منخفضة حسّاسة للنسيج، والنسيج هو ما يمتصّ علامات العنف، لكنّه

في الوقت نفسه يُنسج طيلة الوقت، إنّه الحياة. ليس هناك نوستالجيا

ولا مرثاة لدى فرح. الجماليّة مُحكمة، وكأنّها شكلانيّة، تجمع بأسلوب

تصنيف غير هرميّ أعمالا مصوّرة من فيلم فيديو وصورًا فوتوغرافيّة

مختلفة، المنخفض ينسجم في المرتفع، العالي في المنخفض، الموضوع

في الذات والجماد في الحيّ والجسد. محافظة على استقلاليّتها بطريقتها،

ترتبط، مثل وحدات من الذاكرة التي تحمل شيفرة تحليل، في مبنى مؤقّت

من «زمن-الآن » – مبنى مؤقّت في أحاديّته الهشّة، ولكن غير القابلة

للتآكل.