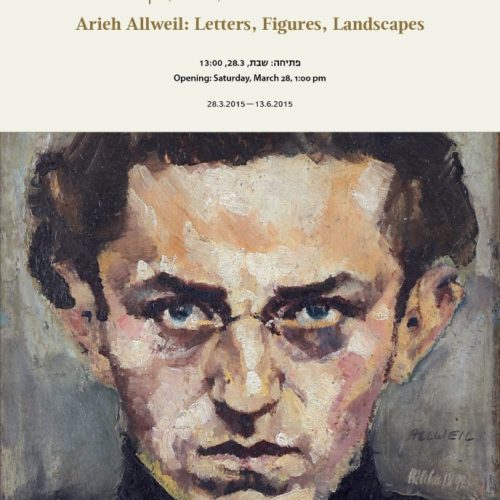

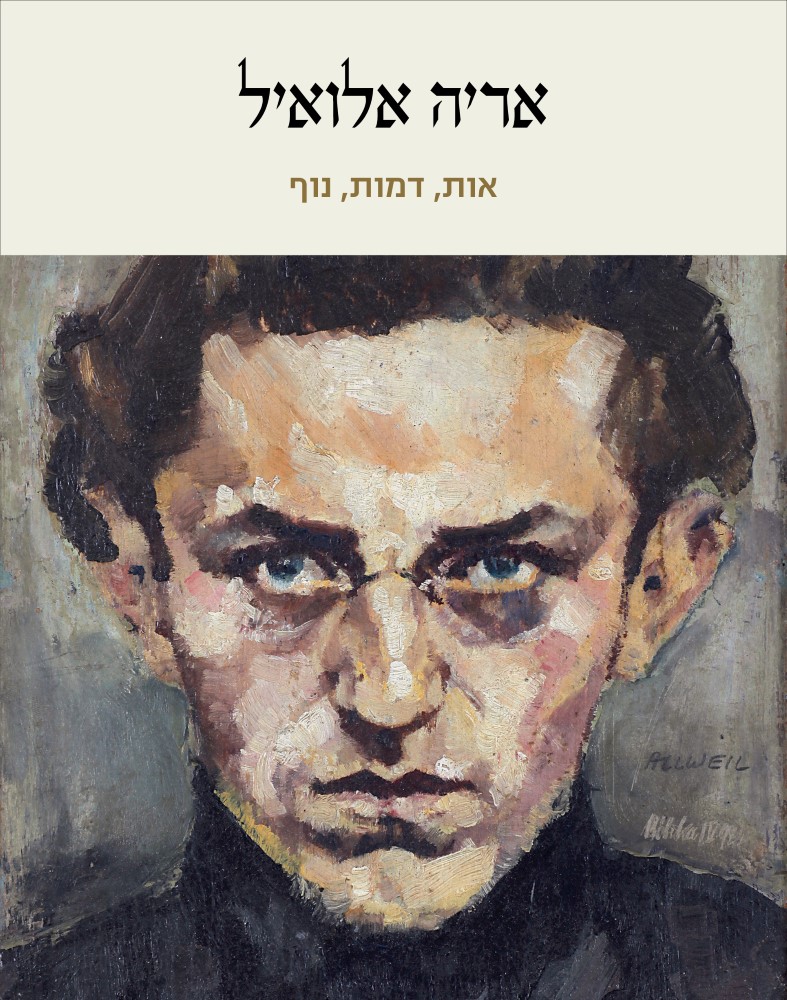

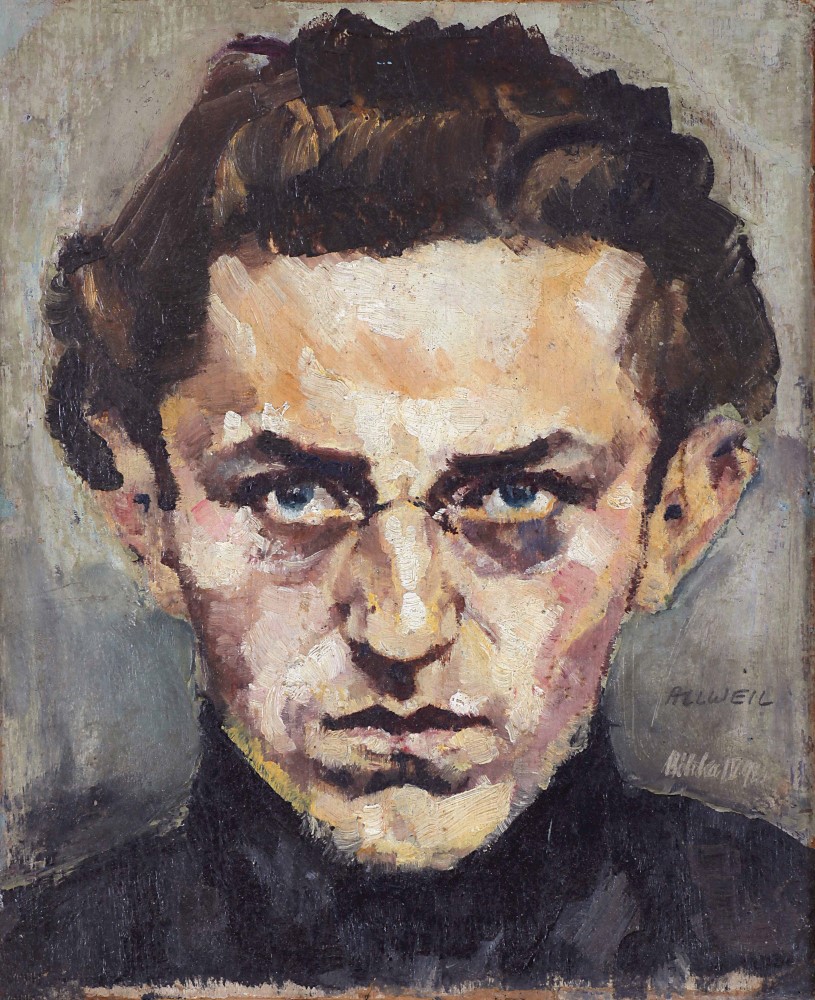

The retrospective exhibition of Arieh Allweil, which is on show in the spring of 2015 at the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod, is accompanied by a comprehensive book that embraces all the phases of his oeuvre. The artist’s life story evokes a particular connection with this museum because of its place in the history of communal settlement: Arieh Allweil, a leader of the Hashomer Hatzair group that settled in Bitaniya Ilit on 1920, was a central figure in a communal settlement which became known as one of the most challenging ever attempted in this country – and which later became the subject of a play, The Night of the Twentieth, which has itself become a myth. Allweil, an artist and a leader, chose a life of art, set out to study art at the academy in Vienna, did exceedingly well there, joined the “Kunstschau” group of artists which included Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, exhibited with them in the ’20s, and created early works some of which – such as his Gray Mountain series – have recently attained renewed recognition.

On his return to Palestine in 1926 he became an artist and a teacher. He was one of the founders of the Tel Aviv Museum and of the Midrasha Art Teachers’ College when it was first established in Tel Aviv.

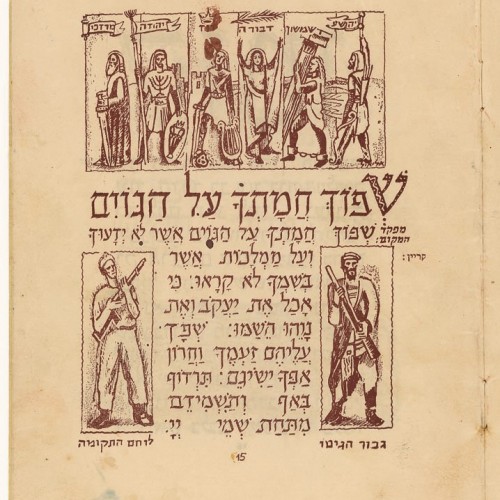

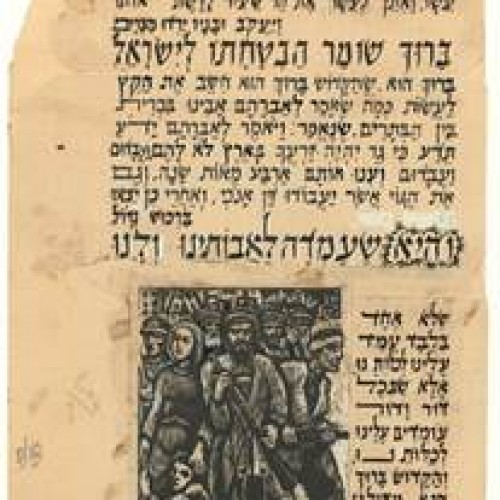

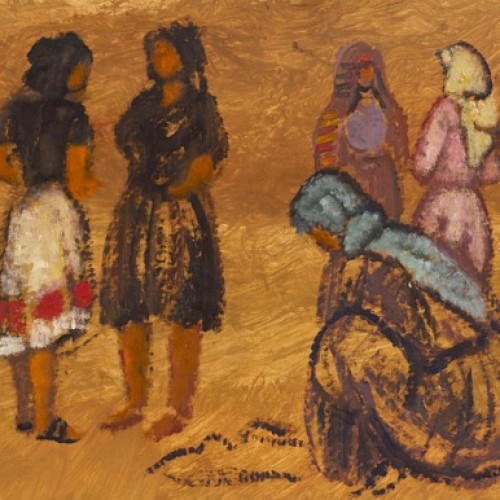

Allweil made a distinctive contribution to Israeli art in two very different and contrasting fields: a new visual interpretation of biblical texts by means of black-and-white prints and calligraphy, in works that in a unique and topical way express his suppressed anguish at the horrors of the Holocaust period, and an original development of richly colorful and pictorial landscape painting, which proposes a new kind of landscape painting, different in its conception from the kind of painting that had become established in the mainstream of Eretz-Israeli and Israeli art. The dialectical relations between these two orientations in Allweil’s oeuvre, nightmare and utopia, hint at its complex character and constitute the basis of the exhibition and the book.

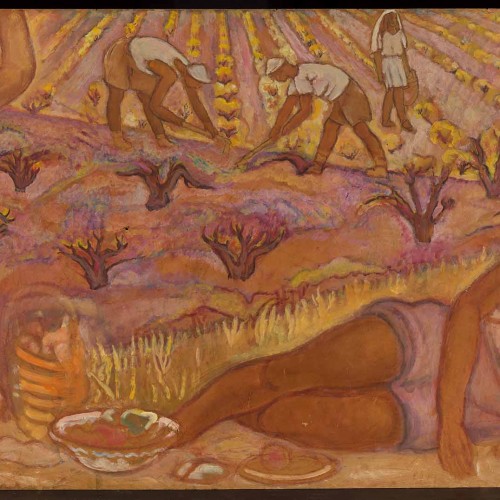

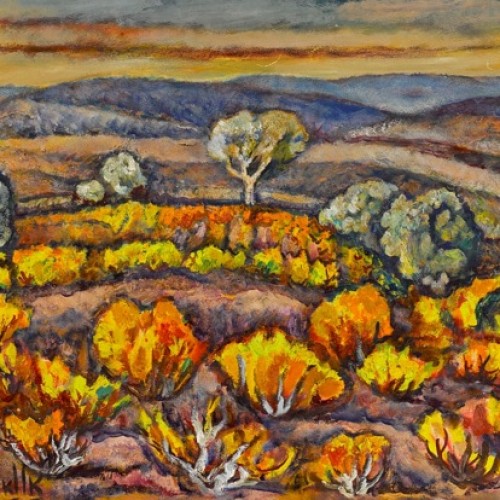

In 1939 Allweil established an independent publishing firm named “Hillel”, and in the course of the war years and the Holocaust he published books that he produced with his own hands, among them The Anonymous Jew, Lamentations, Amos and Esther. He hand-gouged the texts on linoleum, interspersed the illustrations with allusions to events of the period, printed the sheets, cut, folded and bound the books all by himself. In 1967 he retired from teaching, purchased canvases and materials, and planned to devote all his time to painting. In the spring he set out to paint the flowering landscapes on the slopes of the mountains of Safed, where the skyscape is almost absent and a purplish color is dominant. The color planes in these last painting are soft and fluffy, and the light is captured in them in paint thinned with white, similarly to the soft and pale planes of his early confrontations with this country’s landscapes on his return from Vienna. This series of landscapes of spring flowering around Safed was the swansong of his oeuvre; he felt ill, was diagnosed with heart failure, and on the eve of Passover he had a heart attack and died.

Arieh Allweil’s many-layered oeuvre has not been given its rightful place in the story of Israeli art. The retrospective exhibition and the book reveal the work of an inspiring, innovative, and committed artist.