“Every day the sun rises and in the evening it sets, but some time passes before the stars come out. Between sunset and the time the stars come out there is the twilight of evening, which continues until the sun has sunk deeper than six and a half degrees below the horizon. At our geographical latitude this twilight lasts for about half an hour, and in countries closer to the pole it lasts longer.” – Asher Erlich, Guide to the Sky of Our Land (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv, 1959

“Six and a Half Degrees Below the Horizon” – the title Noam Rabinovich has given his series of maps – may be physically accurate for the position of the sun around the time the maps relate to, but it also carries a poetic and metaphoric meaning.

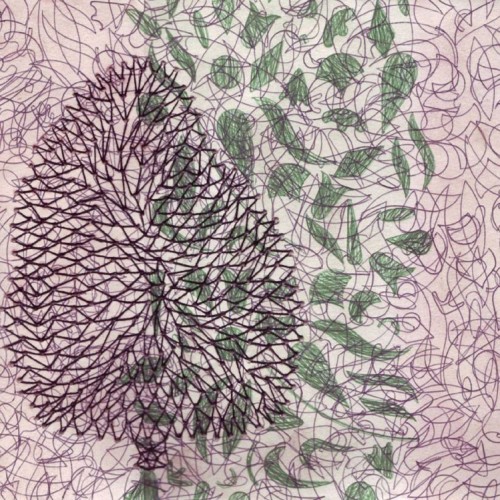

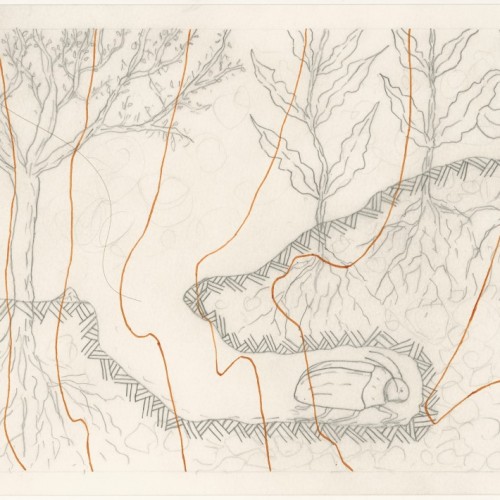

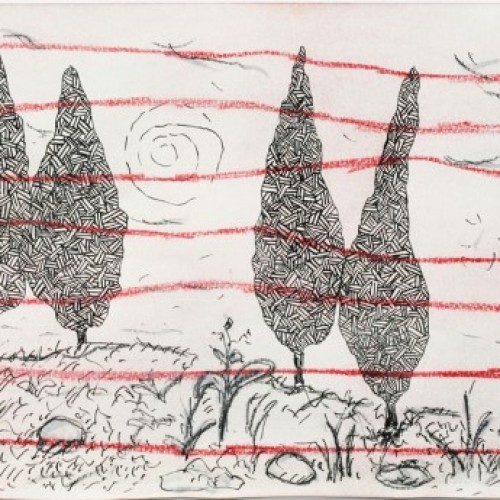

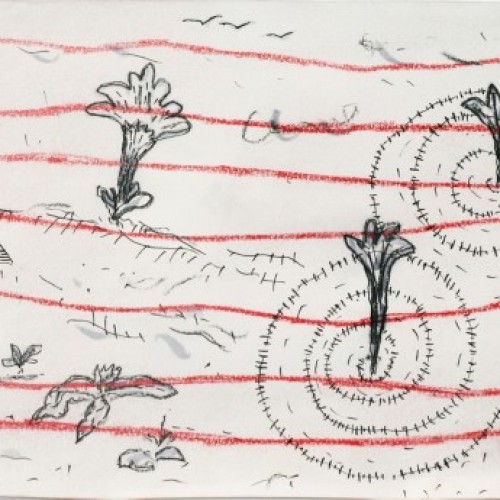

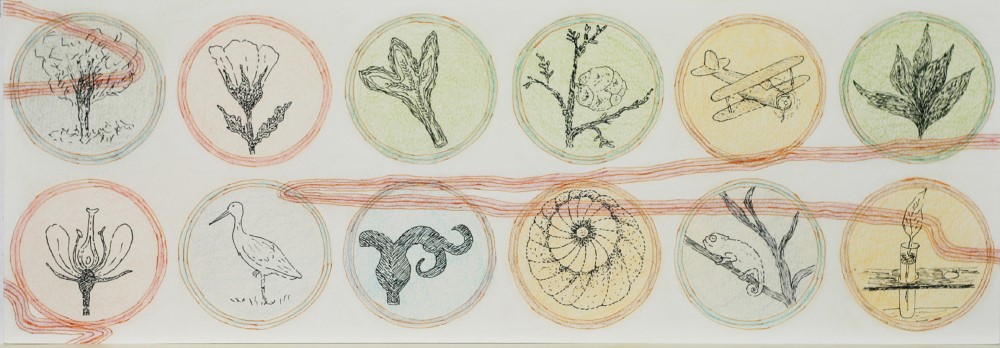

If the time of the maps is the time that follows sunset, the local mountains are a point of departure that is assimilated deep into the body of his work. In the maps we can find lines of altitude and cross-sections of a local wadi at the outskirts of Kibbutz Beit Hashita that looks towards Kumi Hill and the eastern Jezreel Valley. The artist has adopted this wadi since 1980, and it is there that he works. The work method Noam has developed connects his prolonged stays in the wadi with work in the studio, juxtaposing poles of experience in the landscape as a site of memory. In the studio the landscape is translated into the lines of the map, and the map into a journey to a terrain that is simultaneously “a precious spot in the mountain’s bosom” (Zerubavel Gilead) and a landscape that also bears traces of “the day of toil and a night in the line of fire” (Natan Alterman). This is a complex and invented landscape, a landscape of past and future in which layers of nature and culture intermix, with echoes of daring adventures, of burrows deep in the earth, of a gaze hovering at a low altitude above the ground, of a horizon with a familiar silhouette of Kumi Hill, of cypresses and sabra cacti, plum trees and a palm tree.

In one of the maps the nature is alive, laid out with codes that evoke a longing for childhood books about a pristine nature untouched by evil, and in another the landscape is crisscrossed with barbed wire, a squashed vehicle and traces of events that blend into the always passive landscape. At times the painted map recalls a map in a sandbox with miniatures in a life-and-death game of soldiers, but at other times the space of the map contains a disaster, like a constitutive childhood trauma, or sights of a catastrophe that convey the horror of the deceptive tranquility as self-evident, with a simulated equanimity of after it is all over.

Noam Rabinovich’s inverts the concepts of map, landscape, nature. Actually, he was never a landscape painter or a nature painter, even though that is the basis of his work as an artist. What is distinctive about his work is the way he confronts the problematics of the local landscape – with the Gordian Knot that ties landscape to ideology. He has created a language of models of nature that has enabled him to embroider, concretely and also metaphorically, an intimate world layered with inner affinities – multi-disciplinary affinities, collective as well as private, culture, nature and landscape inseparably joined together in this place and at this time. The in-between time of these maps connects image with background, sets models of nature in a context of landscape, proposes a neutral framework of mapping sections of ground to contain a nightmare in utopia.